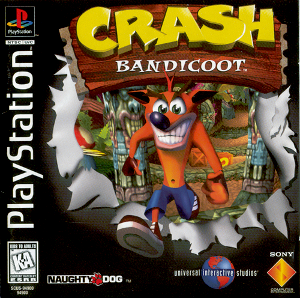

My first experience playing a video game started out as being fun, then exploratory, then pitiable. I honestly do not know how old I was when I played Crash Bandicoot (1996) for the Sony Playstation, but I do remember rage quitting and crying  with frustration whenever I

with frustration whenever I  could not get passed the second level; I used to have nightmares about the main character Crash dying. Looking back, I guess my constantly trying to get passed the second level and the subsequent rage quit indicated how

could not get passed the second level; I used to have nightmares about the main character Crash dying. Looking back, I guess my constantly trying to get passed the second level and the subsequent rage quit indicated how

immersed I was in playing the game.

I found Colby and Colby’s (2008) article and Alberti (2008) article interesting because of the recurring topic of play, which I think is the core purpose of a video game. These authors write about play and its application to reading and writing pedagogy. Alberti seems to lean toward play and reading, but Colby and Colby’s article attracted me the most because of their theories on play and writing pedagogy in particular.

Colby and Colby suggest that “gameplay becomes an important part of the invention process” (310). When I was playing video games, I had to go through lots of discovery, trial, and error in order to build a gameplay learning experience. In relation to the authors’ aforementioned claim about what gameplay entailed, it occurred to me that part of the invention process when beginning to write something is the playing involved. That is, students have to formulate, adjust, and go through trial and error with their ideas. During the process of invention, students are discovering things—what works, what does not, and what needs to be done in order to progress. While I did not have to go through an invention process, in my conquest to get through the first level of Crash Bandicoot, I had discovered many things: square holes in the ground meant that I had to jump over them to proceed otherwise I would die, boxes held “wumpa fruit” that I could collect and if I collected 100 I could earn an extra life, enemies would be in my way, and I had to time my spins or jump on them in order to kill them or else I would be killed. While I could have just read through the instructional booklet (I did not do so before playing), now I do not regret it because going in blind allowed me to discover, explore, and fully immerse myself in the game (until I started rage quitting.) I feel that I had a richer learning experience this way. I can imagine that “going in blind” in a video game is similar to the state student writers go through when first given an assignment prompt because going in blind forces students to go through the processes of invention and discovery—they need to play—in order to proceed. Playing then, in the world video games and composition, is a tool players and students use as a way into the task before them.

Alberti claims that there is a “game of reading and writing” (p.268) and within the game of reading and writing, there has to be some sort of play involved. Colby and Colby illustrate what it would be like to incorporate WoW in a complex curriculum, and play is definitely involved; in fact, if students who have never played WoW went into this class, they would have to go through an extensive version of my discovery process due to WoW’s immersive world and gameplay. I cannot really see WoW as the most ideal video game because the complexity of the game’s world almost requires students to be familiar with the game and everything that it entails before the first day of class otherwise precious time will be spent trying to learn the game’s basics. As future teachers of composition who value diverse content, I wonder, though, what other video games or video game genres besides the MMPORPG could also bring about student (or even teacher) learning experiences that Alberti and Colby and Colby discuss and envision? Since we would be dealing with different video games, what and how might these other video games shape reading and writing pedagogies in the classroom?

With this group of reading, I instantly started comparing the differences between blogs and wiki pages. Generally, blogs are written by one author and have content that is open for criticism by outsiders. According to Tryon, students become better writers because of this instant publication of their writing. Through this instant publication, students are capable of escaping the perception that they are “passive consumers” of writing and instead are becoming “active participants” of a specific writing community (Tryon 128). In the case of Tryon’s experience with his “Writing to the Moment” course, he was lucky to have readers outside of the classroom comment on his students’ blogs. As intimidating as that may be, this aspect of the course blogs made it so much more impactful for Tyron’s students because it showed an establishment of his students becoming part of that community. Rather than having the criticism in the comment section bring down their writing, students were able to strengthen their writing by incorporating the criticism into their next writing or using it to further establish their stances present in the blog; “blogging’s ephemerality, its focus on the everyday, and its no-holds-barred argumentative style” (128).

With this group of reading, I instantly started comparing the differences between blogs and wiki pages. Generally, blogs are written by one author and have content that is open for criticism by outsiders. According to Tryon, students become better writers because of this instant publication of their writing. Through this instant publication, students are capable of escaping the perception that they are “passive consumers” of writing and instead are becoming “active participants” of a specific writing community (Tryon 128). In the case of Tryon’s experience with his “Writing to the Moment” course, he was lucky to have readers outside of the classroom comment on his students’ blogs. As intimidating as that may be, this aspect of the course blogs made it so much more impactful for Tyron’s students because it showed an establishment of his students becoming part of that community. Rather than having the criticism in the comment section bring down their writing, students were able to strengthen their writing by incorporating the criticism into their next writing or using it to further establish their stances present in the blog; “blogging’s ephemerality, its focus on the everyday, and its no-holds-barred argumentative style” (128).