Konami’s Contra: political overtones or nah?

The field has lent rather serious consideration to more “traditional” formats, such as traditional, print-based texts, film, and even music and dance. Many of us have expanded our consciousness of what it means to compose, and what, actually a composition actually “is,” and we find a tremendous amount of variation and a sense of displacement in attempting to construct a fixed definition or sense of what makes a composition well, a composition. Having been an avid gamer for much of my life and an avid reader of literature, you can imagine my preoccupation with the narrative aspect of both forms and how might we introduce video games into the classroom.

Of course, the easy, “no brainer” approach would be to consider video games as just another narrative format, which is sort of the approach that many film/cinema courses have taken; one need not look further than the proliferation of “film as literature” courses on high school and college campuses everywhere, or the landmark text, A History of Narrative Film as evidentiary support of this evolution in esteem and perceived academic value. It would then be amiss not to consider video games, but I would like to point out that video games are not simply another narrative form, but are rather a unique genre of narration that complicates our current understanding of narratology in a meaningful manner that should be explored in an academic context as any other “worthy” discipline.

Gee states that we “never just read or write; rather, we always read or write something m some way,” and in video games, that “way” is through the player him or herself. Gee writes, “We have this core identity thanks to being in one and the same body over time and thanks to being able to tell ourselves a reasonably (but only reasonably) coherent life story in which we are the “hero” (or, at least, central character). But as we take on new identities or transform old ones, this core identity changes and transforms as well. We are fluid creatures in the making, since we make ourselves socially through participation with others in various groups.” Gee is touching on an aspect of gaming that is not entirely divorced from other narrative conveyances, which all depend on a minimum level of empathy between reader and character, a relationship between reader and text. On that note, the customization of characters in recent role playing games such as Mass Effect enable players to create identities that may reflect deep-seated beliefs that are more representative of their “true” identities that they might not otherwise feel comfortable showing; this conscious selection of identities additionally enables exploration of occupation, gender, and sexuality that would otherwise be impossible or difficult.

Male or female Commander Shepard? The choice is yours and you can customize him/her.

Additionally, video games are distinctly powerful in that the way the virtual reality is constructed narrows the “distance” between the reader and the “text” — we unconsciously associate ourselves with the characters without a second thought; when the character we are controlling dies and someone asks us what happened in the game, the first thing we tend to say is, “ARGH, SHIT! I DIED AGAIN!” The perspective instantly becomes first-person, whether or not the game’s design attempts to mimic the first-person visual orientation.

When Gee discusses semiotic domains and specifically, the way in which the player can interface with a virtual reality through which an affiliation can be developed, within the game and outside of it via affinity groups related to the game or genre of game itself. The construction of meaning depends on the player’s ability to interact within the digital space, which, through its multimodality, emulates different aspects of real-life experience in such a manner that other formats simply cannot. These “technical semiotic domains,” as Gee calls them, are in contrast to “lifeworld domains,” where people operate as their everyday selves, and not as members of specialist groups.

Video games are not individual endeavors, nor do the experiences they facilitate imply any sort of isolation, despite popular claims in mass media. Rather, video games externalize specific narratological processes (e.g. instead of thinking about the perspective or interaction and imagining it in your mind as you read a book, you are controlling your character with a controller) and foster communities, either in real life or more commonly today, over the Internet and cyberspace, with network gaming. These relationships are both real and imagined, and as such, are paradoxical, but when games are of quality and gamers approach these games with the same level of sophistication and engagement, “the content of video games, when they are played actively and critically… situate meaning in a multimodal space through embodied experiences to solve problems and reflect on the intricacies of the design of imagined worlds and the design of both real and imagined social relationships and identities in the modern world” (Gee).

This can be especially powerful today when we have video games such as Infamous, Mass Effect, Witcher 3, and so on, where the gamer must make moral and ethical decisions that may carry consequences in the narrative. These games have “karma” or “morality” engines that will open certain narrative paths and bar others. Ian Bogost’s article, “The Ecology of Games” featured several interesting claims, one of which theorized that we can learn to read games “as deliberate expressions of particular perspectives. In other words, video games make claims about the world, which players can understand, evaluate, and deliberate.” I believe that as games become more advanced and the hardware develops to accommodate more realistic and consequently, more relevant “expressions,” gamers will be able to find real intellectual value (if they haven’t already), and scholars will come to recognize their equality and in some ways, superiority, in promoting critical thought processes in the audiences who have attained the literacy to navigate these virtual, interactive stories that negotiate and redefine the boundaries of narratives, authorship, and discourse (community).

Example of “karma system” in Infamous.

Unlike the 16-bit video games from the early days that, although somewhat empathetic for gamers were distanced due to technological and graphical limitations, it is today and in the future, more than ever, that the potential for video games to rise amongst the ranks of other more entrenched narrative/compositional platforms can be realized in the academy. Finally, as Bogost claimed, “game developers can learn to create games that make deliberate expressions about the world,” and we have an obligation to lend those expressions equal weight in the academy and in the classroom.

Because of the multimodal nature of video games and all the many ways they can engage with us and emulate real-world experiences like no other platform, video games have the potential to transcend traditional formats and mimic waking life with an ironic authenticity that may unite the semiotic domain that is packaged within the game with the semiotics of existence.

with frustration whenever I

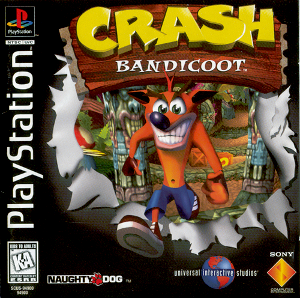

with frustration whenever I  could not get passed the second level; I used to have nightmares about the main character Crash dying. Looking back, I guess my constantly trying to get passed the second level and the subsequent rage quit indicated how

could not get passed the second level; I used to have nightmares about the main character Crash dying. Looking back, I guess my constantly trying to get passed the second level and the subsequent rage quit indicated how