Video games have been a major part of my life experience ever since I was able to hold a controller and barely move and jump in Super Mario Brothers or swing a sword in The Legend Of Zelda for the NES.

Sources: Rebubble and Nitwitty

My experience with gaming has evolved over the years from home consoles to handheld devices to PC gaming. I have spent around 7 of the last 10 years of my experience with gaming has evolved over the years from home consoles to handheld devices to PC gaming. I have spent around 7 of the last 10 years of World of Warcraft’s (WoW) existence playing the game as well as playing League of Legends, Hearthstone, and other multiplayer games and I would love nothing more than to find a way to incorporate video games or game design concepts into the classroom on some scale. From digging into writings by pieces by Bogost, Alberti, and Gee on what we can learn from gaming, game design, and gaming concepts, I was sure that introducing these kinds of concepts into the classroom could be wildly successful. I was all ready to pop the champagne and celebrate, but then…

I really wanted to write an entirely positive article, but I guess I am too enticed by challenging academics at their assertions because once I started reading the Colbys’ article I slammed on the proverbial brakes and turned that celebration car around, faster than you could say “LEEEEEEEEEEEEEROY JEEEEEEEENKINS!”

And on that day, a meme was born.

“A Pedagogy of Play: Integrating Computer Games into the Writing Classroom” by Rebekah Shultz Colby and Richard Colby weaves an idyllic world where they could advertise a class in which the entire class would spend the semester playing Blizzard Entertainment’s wildly successful and still very popular game, WoW, and I am here to try to (probably unsuccessfully) tactfully explain why this would be a terrible idea that would not work outside of isolated cases. Maybe this type of class is not supposed to be adopted in any significant way in a school system. I find that kind of exclusivity to be a bit reprehensible, which is why I am so incensed at the notion of WoW or any high-intensity computer game, being used as the core aspect of a classroom.

If my work at community colleges and life as a student has been any indication, many students would not have the resources to be able to take the opportunity offered by this class. Sure, at Denver University, a private college where tuition currently sits at around 15,096 dollars a semester, students might be able to afford a computer with the capabilities necessary to run WoW well enough to play the game. However, if implemented where I live, go to school, and work, I do not believe this would be the case. While many students have laptops, most of them are basic machines that are built with only the bare essentials to utilize programs like Microsoft Office, Facebook (maybe casual games on said website), and content streaming services.

Given these choices, many would take the HP. Credit: Freebies2deals

Predominantly, these are the kinds of computers that are advertised to students by stores like Best Buy: non-gaming computers with no dedicated graphics processor that would barely run the game if at all. One would need to buy a laptop that costs around $700 to run the game in a way that is playable. Further, WoW requires its own monetary subscription of $15 a month after you buy the game, which, at this current moment, involves spending at around $40 to purchase the game and the most recent expansion. I would fear that students would not be totally clear on what they would need when signing up for a class like this and then have to drop, leaving them sans an important class for their GE. None of the financial aspects of this endeavor are examined in the paper; the authors only made the point that “WoW has relatively low system requirements.” Send a message to any PC gamer and ask them if playing on the lowest settings makes a game fun to play. The answer you will probably get is:

This class concept is not feasible or accessible to the larger student population of an American college campus, especially community colleges.

I would also question a student’s time dedication to be able to participate in this class. Unless you are already an avid WoW player, which the paper identifies is not required, there is a huge amount of time that a player must commit to gain expertise in any aspect of the game without putting in a significant amount of research on other websites (and I would argue that both of these are required to be able to contribute to a wiki or make a guide on the game). For some students, playing the game might take far in excess of the expected time, and, even then, I would be concerned how much time would be required to play the game in addition to time spent doing the various class writing assignments. Leveling a character, finding and immersing oneself in a guild, leveling a profession, and learning how the mechanics of the game work take hours upon hours of play and research even in the current version of the game which is MUCH simpler than it was in 2008 when this article was published. Most active guilds will not look at you twice if you are not at or near max level and player interaction is minimal outside of a guild. In addition, you just do not learn enough about the game or its community at low levels.

This is my most recent character and I have not even gotten him to max level.

And I sort of know what I am doing half the time.

The Colbys only identify two cases of students in this experimental class environment, “Josh, an experienced WoW player” and Tiffany who had a roommate who played WoW often and took the class with her. I was disappointed by the lack of other representative experiences for this proposal of a WoW classroom if a student was not a WoW player. There was no real consideration of what to do if one or more of the students in the class decided that they did not like the game besides the result of dropping, which, again, really punishes the student.

I honestly do not know of a massively multiplayer online style game that would dodge both of these serious issues with this pedagogy. I want to love this idea. I REALLY want to. But just like any game community, even if one could find a way to make this work, I doubt its longevity. Semester to semester a teacher might have to find a new game or gaming community as games die and a new fad emerges. When this article was written WoW was the biggest PC game that had ever existed boasting around ten million subscribers, but now the game has less than half of that number and seems to still be declining.

Now down to around 5.5 million subs.

A multiplayer online battle arena (moba) like League of Legends would be the WoW of today, but who know how long that game would last (Nor would I ever subject my students to that game’s community. I have been called every slur, profanity and disgusting use of language imaginable when I am playing badly in that game. It is the YouTube comments section of video games. Only click this if you want an example. It is not safe for work because of the intense language.)

Gaming is definitely a New Media Literacy that, as time passes, more and more students will be playing in some fashion. Involving games, game design, and gaming rhetoric in the classroom is worth studying. Programs like Classcraft are already paving the way for creating augmented reality games in the classroom environment. To me, this is the most exciting use of the excursions composition academics have been making, in addition to using video games as a way of studying rhetoric and genre in the classroom.

I think it is about time to end this rant and hope that this even fits the bill for this blog. I leave you again with an OC remix of the week. This is Legend of Zelda: ALttP ‘Come to the Dark Side, It’s a Funky Place’ by Nostalvania:

with frustration whenever I

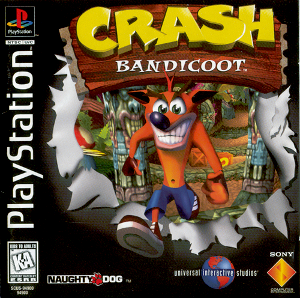

with frustration whenever I  could not get passed the second level; I used to have nightmares about the main character Crash dying. Looking back, I guess my constantly trying to get passed the second level and the subsequent rage quit indicated how

could not get passed the second level; I used to have nightmares about the main character Crash dying. Looking back, I guess my constantly trying to get passed the second level and the subsequent rage quit indicated how